In March 2023, the SEC charged eight celebrities with violating certain provisions of the Securities Act of 1933 in promoting cryptocurrency assets. The charges stem from Section 17(b) of the Act, an anti-fraud and advertising provision that addresses the non-disclosure of payments in connection with promotional activities.

The group of celebrities – including Lindsay Lohan, Jake Paul and Ne-Yo – was specifically accused of illegally promoting Tron (TRX) and/or BitTorrent (BTT) tokens offered by companies led by Tron founder Justin Sun.

While the SEC won the case, the core questions remain unanswered: Where does pricing a cryptocurrency end and promoting it begin? Is there such a thing as legit cryptocurrency promotion? And what determines the status of the asset as collateral?

Other ongoing legal battles related to the illegal promotion of crypto — including those involving celebrities who endorse FTX such as Tom Brady, Larry David, Stephen Curry, and others — revolve around the same crucial questions. With over 20 percent of US consumers owning and using crypto, it is clear that clear lines need to be drawn when selling and promoting digital assets.

So true is that line? And is there a legal difference between merely supporting a specific digital asset and unlawfully promoting it?

“Reasonable consumer/investor” vs. public figure/celebrity

At the most fundamental level, the first question to ask is how do we define what it means to “patronize” and support a particular digital asset – where an individual simply shares their investment holdings with family, friends and colleagues – versus what it means to “promote” specific digital asset to a large community with the specific intent of persuading another to invest their money in that individual asset.

Patronizing a digital asset isn’t much different from a person simply sharing their shares with a family member, friend or colleague. In this case, we have to assume that the average consumer does not fully understand the mechanics of cryptocurrency, how it works and the laws surrounding it – especially since the laws and regulations surrounding it are almost non-existent when it comes to the sale and promotion of digital assets.

So, what is “tipping” the scale from an individual sharing harmless excitement about a particular digital asset to taking a substantial step in wanting to create an “economic dependency” of such magnitude that the SEC crossing territory?

It appears that the specific facts and circumstances of the promotion are based on the following:

(1) who you are as a person/company,

(2) the means at your disposal to intentionally communicate and promote the asset,

(3) the likelihood that your message/promotion will reach a large community of people, and

(4) the likelihood that the message/promotion will strongly influence a third party’s decision to create an economic dependency and financial decision based on your social status.

To address the first element of “who the promoter is”, it would make sense to apply a “reasonable person” standard, which would draw the line of whether we are talking about an ordinary consumer (experienced or novice) or a public figure/celebrity, which brings additional weight and responsibilities.

In most cases, it appears that a reasonable, average consumer who supports and shares their investment in a particular digital asset is (in most cases) unlikely to do so in the expectation that they will help drive the floor or market price of that particular asset increase. possess.

#TRX

@justinsuntron https://t.co/xh6xB6fNmo

— Jake Paul (@jakepaul) February 13, 2021

A public figure or celebrity, on the other hand, through and through its “public” status, has a uniquely powerful ability to communicate a message or idea in general that has a very high probability of persuading huge amounts of people to act or behave in a way – no matter how experienced or skilled they are at being able to convey such a message accurately.

For this reason, identifying who is actually promoting the digital asset is crucial when assessing the “why” behind their promotion and whether it is an “illegal promotion” under current securities laws.

The “look and feel” of the action

Another important aspect in determining the difference between patronizing and promoting is the look and feel of what is being shared. We’ve seen the SEC crack down on celebrity approval of digital assets ultimately speaking to the look and feel of the celebrity’s promotion of a cryptocurrency, including the verbiage and nature of the disclosures specifically expressed in the post .

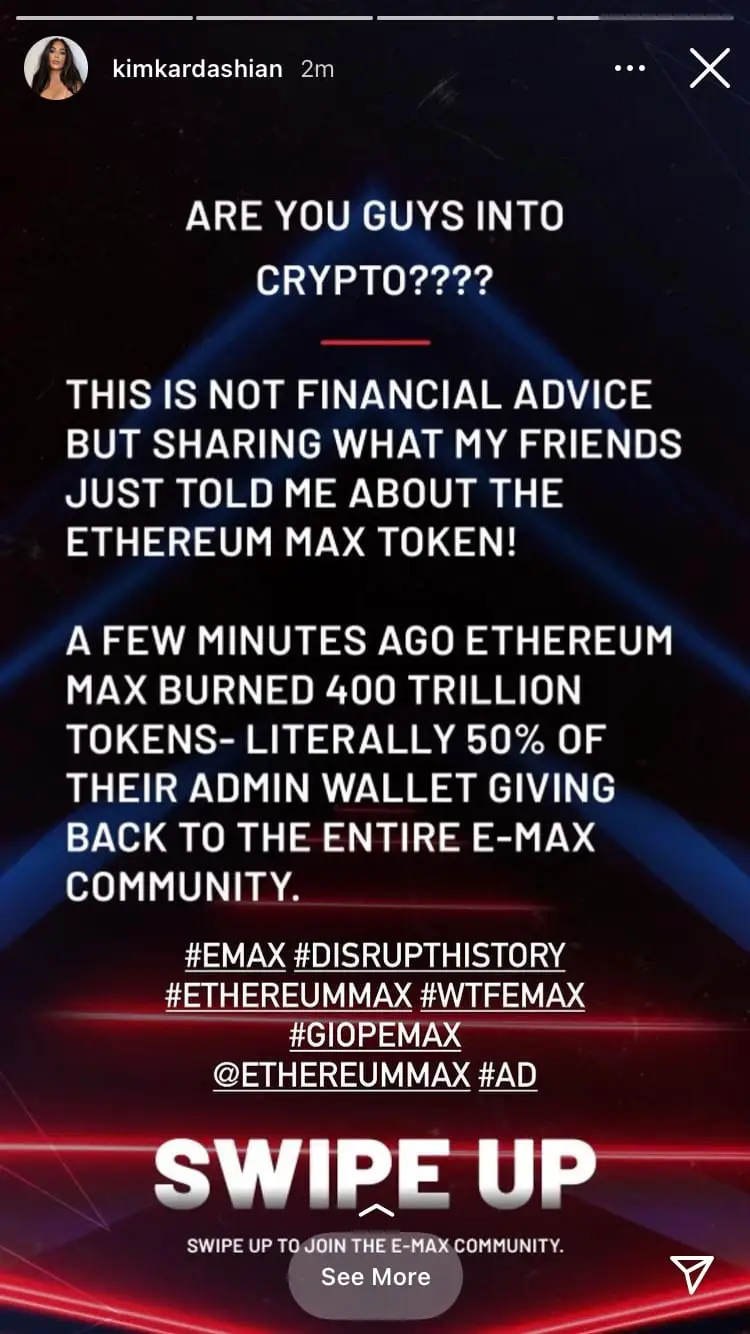

This started in October 2022 with Kim Kardashian and her illegal promotion of EthereumMax (EMAX).

While Kardashian agreed to settle the suit and paid $1.26 million in fines, remission and interest, the SEC found that Kardashian had failed to disclose that she had been paid $250,000 to publish a post on her Instagram account in 2021 (which now has 359 million followers). about EMAX tokens.

Her message included a link to the EthereumMax website, which provided instructions for potential investors to buy EMAX tokens, but nothing else. Although Kardashian had stated in her post that it was “not financial advice,” in addition to adding several hashtags, including “#ad,” the SEC said that wasn’t enough for compliance.

Other celebrities targeted by the SEC included Floyd Mayweather, Jr., DJ Khaled, Lindsay Lohan, Jake Paul, Soulja Boy, Akon, Ne-Yo, and Lil Yachty for the same reasons.

thanks guys, bought some BNB, DGB, TRX, KLV, ZPAE and FDO

now what? let’s go

— Soulja Boy (Draco) (@souljaboy) January 22, 2021

Then, in November 2022, FTX was declared bankrupt, leading to the stock market collapse and one of the biggest financial scandals since Enron and Bernie Madoff.

From Tom Brady, Madonna and Gwyneth Paltrow to David Ortiz, Larry David, Jimmy Fallon and more, the SEC filed suit as FTX’s collapse continued to fizzle out, while also demonstrating the need for public figures to make proper disclosures on their social media posts and TV ads that they are paid to promote these digital assets.

This was a reminder and warning to celebrities and other public figures that they cannot escape the requirements of the anti-advertising provision of Section 17(b) of the Securities Act of 1933, which requires them to disclose to the public when they are paid to promote something, how much they get paid to promote investing in securities.

Section 17(b) prohibits a “promoter” from publishing or distributing an article or communication for “fee received” without fully disclosing that fee. Under the law, a “consideration” is a two-way exchange of value that helps strengthen the enforcement of a legal contract or agreement.

Navigating the unknown

Unfortunately, there is still a gray area regarding the anti-advertising provisions of Section 17(b), as it only applies if the promoted instrument is a “security”. And we still don’t have clear guidelines on what constitutes a “security”.

This brings us to the SEC’s recent sudden crackdown on two of the world’s largest crypto exchanges and the ongoing debate and controversy surrounding the SEC’s “enforce by regulation” approach, which has greatly accelerated the growth and development of the industry. harms.

Senator Cynthia Lummis (R-WY), who, alongside Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), has been a strong advocate for the creation of a full regulatory framework, took to Twitter to share her rock-solid conviction that the SEC “has failed to provide adequate legal guidance on what distinguishes a security from a commodity.”

My statement about the SEC that Coinbase, inc. sues. https://t.co/5KNEM0IPSV pic.twitter.com/EgRIxrIcjj

— Senator Cynthia Lummis (@SenLummis) June 6, 2023

Both she and Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) have been the driving force behind their proposed groundbreaking bipartisan legislation – the Responsible Financial Innovation Actthat would create a full regulatory framework for digital assets that encourages responsible financial innovation, flexibility, transparency and robust consumer protection, while integrating digital assets into existing legislation – such as how so.

The seminal 1946 U.S. Supreme Court case how so is the heart of any traditional securities analysis and presents elements that must be considered to help determine whether an instrument is considered a “security” or an “investment contract”.

An industry-wide gray area

As it stands, this industry is operating in the gray in terms of how they introduce a digital asset to its customer base and the mechanisms underlying its purchase and sale, including the methods they use to promote asset offerings and/or otherwise advertise .

The pending process we now see unfolding will undoubtedly bring those circumstances to the forefront, starting with what criteria makes a digital asset or offering a “security” (versus a commodity) and how a company or brand can legitimately promote or market that asset. to investors and the general public without violating securities laws.

The information in this article does not constitute legal advice and is not intended to be legal advice; instead, all information, content and materials available on this site are for general informational purposes only. The information on this website may not be the most current legal or other information. This website contains links to other third party websites. Readers of this article should contact their lawyer for advice on a particular legal matter. No reader, user or browser of this site should act or refrain from acting on any information contained in this site without first obtaining legal advice from counsel in the relevant jurisdiction.