Blockchain

According to the Center for Alternative Financing (CCAF).

The CCAF, known for estimating the energy consumption of the Bitcoin network over the past few years, says Ethereum consumption totaled 58.26 Terawatt-hours (TWh) between 2015 and the so-called Merge. Switzerland’s annual electricity consumption is 54.88 TWh, while Bitcoin’s is 143.9 TWh, according to the CCAF.

It’s not just the Bitcoin network’s energy consumption that’s a concern for the environmentally conscious. For example, artists exploring the craze for non-fungible token (NFT)-based collectibles have raised concerns about the amount of power required to mint works on Ethereum.

To that end, CCAF has cast its net wider and released the Cambridge Blockchain Network Sustainability Index (CBNSI), an in-depth study of Ethereum’s electricity consumption from a contemporary and historical perspective.

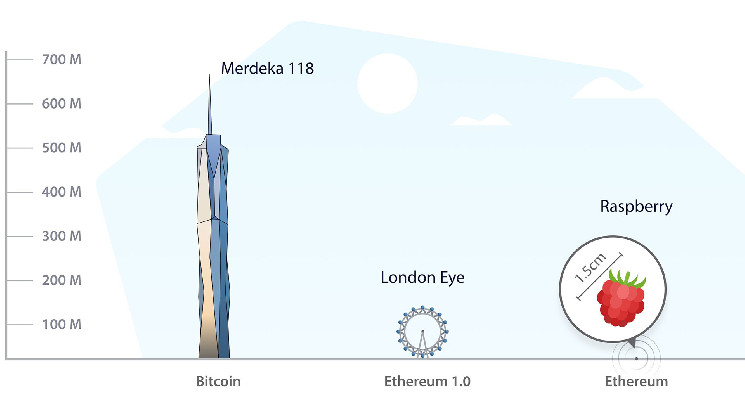

The move to PoS reduced Ethereum consumption by more than 99%. To illustrate the impact of the change, CCAF made a comparison with the height of some well-known buildings.

For example, if Bitcoin’s energy consumption is represented by the Merdeka Building in Kuala Lumpur, the second tallest building in the world at some 678.9 meters (2230 feet), then the previous proof-of-work (PoW) Ethereum mining consensus system is at the comparable level. height of the London Eye, a 135 meter high Ferris wheel. As a PoS power consumer, Ethereum has shrunk to the size of a raspberry, according to CCAF.

As a not-for-profit institution, the CCAF strives to provide public value, hence its creative approach to illustrating energy use, said Alexander Neumüller, CCAF research leader for digital assets and energy use.

“Now if I go out on the street and ask, ‘Hey, what’s 100 terawatt hours? What’s six gigawatt hours?” people don’t know,” Neumüller said in an interview with CoinDesk. “So we tried to contextualize it in the form of images, specifically with the buildings and of course the raspberry. This makes these quantities very clear without understanding energy notations.

While Ethereum’s energy consumption is now an order of magnitude smaller than Bitcoin’s, CCAF is careful not to take a position on which algorithm could be better or worse, Neumüller said. He told CoinDesk that, in his opinion, proof-of-stake is not a perfect substitute for proof-of-work, and many additional factors come into play.

“When you talk about PoW, for example, it is very difficult to attack the network, even if you have extensive financial resources, because you basically have to buy and use hardware and access energy,” he said. “PoS is really more financially based. So if your main goal was to disrupt the network, it would just be a matter of acquiring the native tokens.

CCAF estimates that Ethereum will consume 6.56 GWh of electricity annually. To put that into perspective, the annual electricity consumption of the Eiffel Tower is 6.70 GWh, while burning the light at the British Museum for a year costs 14.48 GWh.

Giving an estimate of Ethereum’s historical energy footprint is useful for projects that might want to start offsetting that debt, which happens to be a post-Merge project underway at ConsenSys. This compensation process is being tackled by a group of Web3 companies now called the Ethereum Climate Platform.

“We decided to take a look back at Ethereum’s seven years of proof of work,” Steven Haft, head of partnerships at ConsenSys, said in an interview. “We looked at our so-called historic carbon debt to see what we could do to clean up our record of emissions over these past years.”